Social topics

How much conversation content is actually social – Human conversational behaviour revisited

Co-authors: Szala, A., Wacewicz, S., Placiński, M., Poniewierska, A. E., Schmeichel, A., Stefańczyk, M. M., Żywiczyński, P., Dunbar, R. I. M., and our wonderful ✨student helpers✨.

This work is supported by the NCN grant UMO-2019/34/E/HS2/00248 and coordinated by the Centre for Language Evolution Studies.

📌 Update (January 2025): The article was published. I consider that to be the official end of this project. However, we already have some ideas regarding the next steps. 🤫 Stay tuned!

📌 Update (August 2024): The study has been accepted for publication in Language and Cognition! 🥳

📌 Update (June 2024): This project was awarded third place 🥉 in the prestigious CLARIN-PL competition rewarding best research work in the humanities and social sciences, recognising innovative and impactful studies that utilise the CLARIN-PL infrastructure.

Pre-registration available here!

How much language use is on social topics? In a pioneering study, Dunbar and colleagues (1997) estimated that “gossip” – understood loosely as “conversation about social and personal topics” – accounted for about two-thirds of time spent on a conversation. This result has been extremely consequential: in addition to its considerable popular impact, it was instrumental in motivating some of the most influential theories of the evolution of the human brain and cognition (the Social Brain theory) and the evolution of language (the “gossip” theory of language origins). However, it is not clear that the theoretical importance of this estimate actually corresponds to the strength of its evidential basis: the authors relied on a relatively small number of conversations (N = 45), collected exclusively in open public environments, between a sample of participants with a very limited demographic and geographic distribution. Secondly, their definition and operationalisation of “social topics” was opaque, as was its connection to the proposed adaptive functions of language.

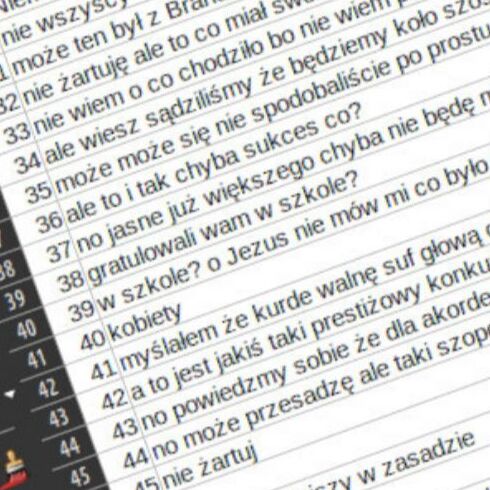

In this project, I revisit Dunbar’s question about the proportion of conversational time spent on discussing social matters with a new set of linguistic-analytic tools, but also with a deeper discussion of what type of language use should count as “social”. We already ran a short study (see: Szala et al., 2022) and found that the ratio of social topics (50.9%) to non-social topics (49.1%) is roughly equal. Based on the conclusions drawn from that study, regarding both the result obtained and the subsequent analysis of the study’s limitations, I expect the study to indicate that the proportion of social to non-social topics is greater than Dunbar’s suggested two-thirds.